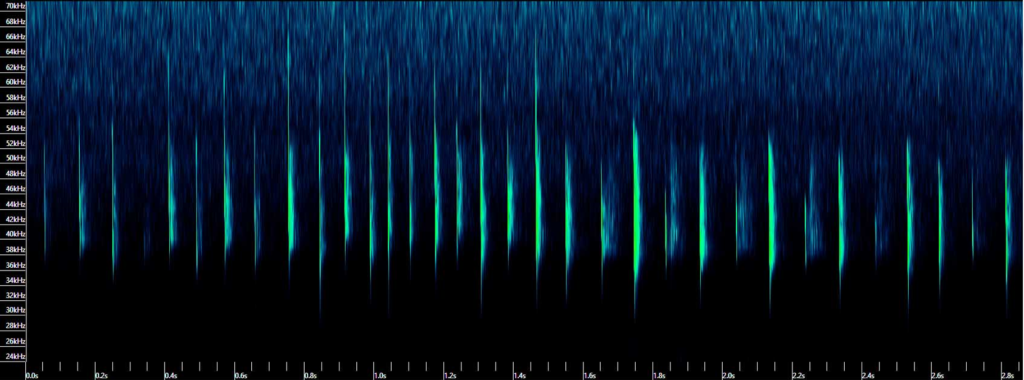

There was fog in the Champlain Valley on Sunday night. At dusk I took a photo of the fog behind the house (Figure 1) and after dark started listening for bats with the Echo Meter Touch 2 bat detector plugged into my phone. During the next 45 minutes the phone recorded 70 bat calls. The fog became denser during the evening and was quite thick by 10:00 PM when bats were still calling (Figure 4). The phone app identified five different bat species including the usual suspects little brown bat, big brown bat, and silver-haired bat, but many of the calls were identified as Indiana bats or northern long-eared bats. That was the first time I had recorded more than a few Indiana bats or northern-long-eared bats anywhere other than at an Indiana bat maternity roosting colony. The phone app can confuse little brown, Indiana, and northern long-eared bats (they are all in the genus Myotis and have similar calls), but regardless there was a lot of bat activity on a rather foggy evening.

In 1971 David Pye published a paper in Nature hypothesizing that fog would interfere with the echolocation calls of bats. In his study, Pye did not observe bats, or test their echolocation calls, or work with natural fog. He made observations in a small container filled with artificial fog using electronic equipment which produced and displayed ultrasonic sounds similar to bat echolocation calls.

This past July, the Secretary of Vermont’s Agency of Natural Resources issued a 15-page decision that the BLSG Insect Control District would not be required to apply for an endangered species permit. Secretary Moore was ignoring the unanimous decision of her agency’s Endangered Species Committee that BLSG’s roadside spraying of mosquito pesticides, which is done after dark when bats are flying, created a risk to the five species of endangered or threatened bats that live and forage in the five towns of the spray district.

An important argument in Secretary Moore’s decision was that bats would not fly into the mist of pesticides. This issue was mentioned six times. More than 450 words were devoted to the argument. The decision referred to Pye’s 1971 paper five times. The Secretary’s conclusion was that because bats avoid flying into fog, they could not be harmed by a fog of pesticides. This is a good argument, unless bats freely fly through fog, which they did all evening on Sunday.

I assume Secretary Moore and the attorneys who wrote the decision had not read Pye’s paper and were just repeating what they had been told by ANR staff. The attorneys should have asked a few questions of those staff members about the following points.

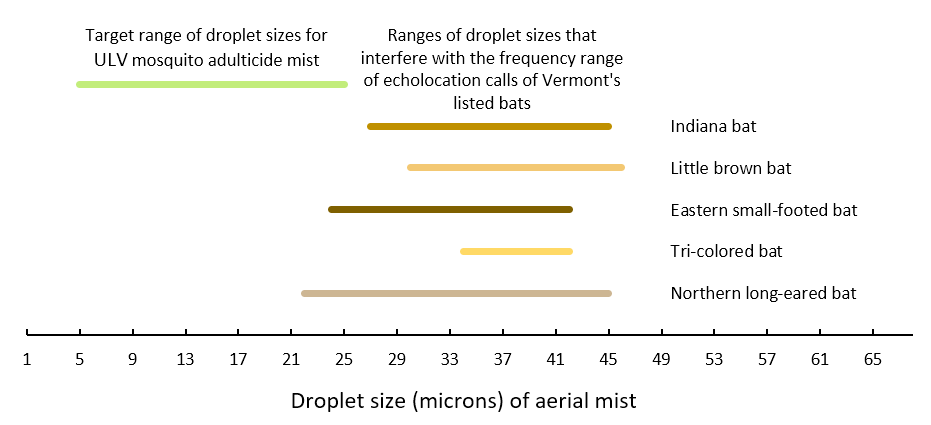

- Fog is not the same as pesticide mist. There is an important difference between natural fog and the pesticide mist sprayed along roads in the BLSG District — water droplets in natural fog are much bigger than the droplets of liquid pesticide produced by the spray district’s ULV (ultra-low volume) sprayers. There can be some overlap, but most natural fog droplets are larger than 25 microns and most ULV pesticide droplets are smaller than 25 microns. One reason the ULV sprayers are engineered to produce tiny droplets is that droplets larger than 30 microns fall to the ground faster where they no longer kill mosquitoes. The ULV mist must stay aloft and spread for an hour or more to kill very many mosquitoes, so the smaller droplets are more effective.

- Bigger droplets interfere more with bat calls. Pye’s 1971 paper presented the physics explaining how liquid droplets interfere with ultrasonic sounds like bat calls. There is a physical relationship between droplet size and the frequency (pitch) of sound that can be interfered with by the droplets. Physics tells us that the calls of Vermont’s bats can be impacted by the droplets in natural fog, especially by droplets between 25 microns and 45 microns (Figure 5). Droplets smaller than 25 microns have little effect on bat calls.

- Natural fog probably has to be very dense to interfere with bats. Pye made his observations with very dense artificial fog in the laboratory and admitted that “natural fogs would be unlikely to give such startling values.” My observations suggest that bats don’t have much trouble using echolocation to navigate and forage for insects in fairly dense natural fog.

- Physics says ULV mist should interfere less with echolocation. My observations indicate that Vermont’s bats can navigate and forage through the large droplets of natural fog, so there is certainly no reason to expect that the smaller droplets of ULV pesticide mist, which have less impact on ultrasonic sounds, would interfere with bat echolocation.

Pye’s 1971 paper presented the hypothesis that fog would make trouble for bats. Pye did not test that hypothesis, but it was published 50 years ago so I checked to see if anyone else had confirmed it. In a half century his paper has been cited a few dozen times mostly by authors describing interesting things about bats, but not by scientists who confirmed that fog is avoided by bats or that fog prevents echolocation. Several studies concluded the opposite, that bats do not change their behavior when it is foggy. There is no scientific agreement that Pye was right about fog being trouble for bats.

One of the publications that cited Pye 1971 was Pye 2021. In a tidy follow-up study exactly 50 years after his first paper, Pye repeated his laboratory experiment. As before, he did not observe bats, or test their echolocation calls, or work with natural fog. He had modern equipment and found the same result but was less confident about his measured impact of fog on ultrasound, admitting that it “is unlikely ever to be realistic in nature” and “the physics needs to be rigorously tested by someone with the appropriate expertise and facilities.”

Secretary Moore’s repeated references to ANR’s misreading of this issue weakens our confidence that her decision was based on sound science or reason. If this was an honest mistake it tells us something about the scientific competence of ANR’s staff. If it was the other kind of mistake, we might have learned something about their professional integrity. Either way, it’s a disappointing lesson.