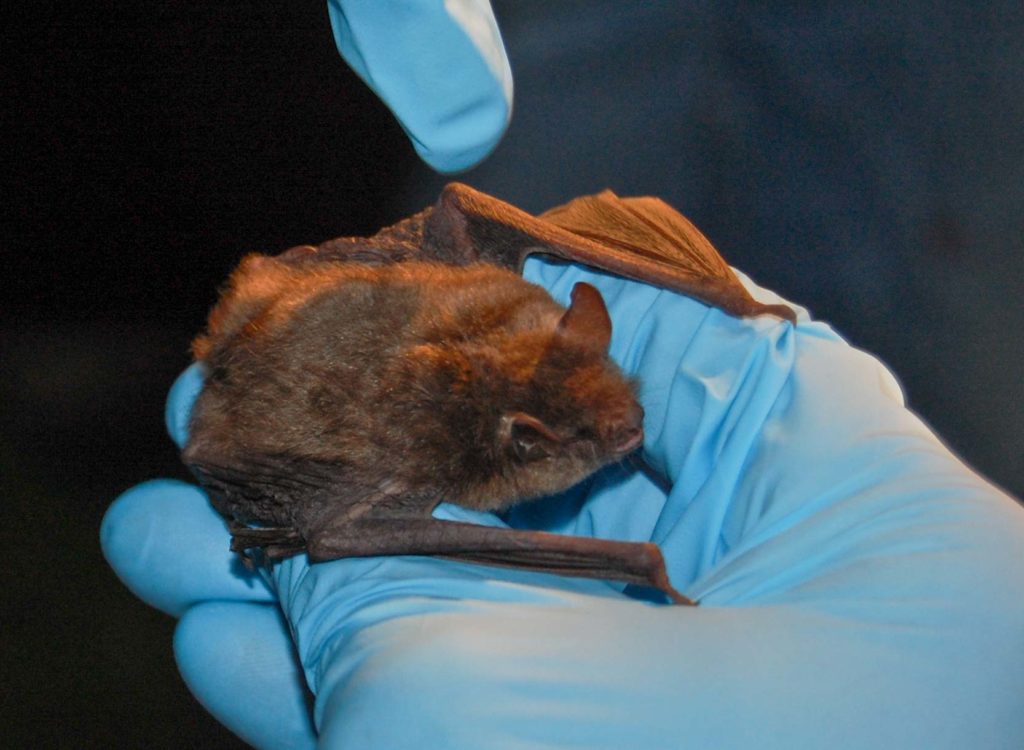

Nine species of bat live in Vermont, and five of them are so uncommon that Vermont has listed them as threatened or endangered species. The Vermont populations of these bats have decreased because of white-nose syndrome, a disease that started killing bats around 2006. All the listed bat species spend the winter clustered in caves or mines where white-nose syndrome can infect new bats.

Two of the state-listed bat species are also rare nationwide and are listed as federally threatened or endangered species. The northern long-eared bat was first listed as federally threatened in 2015 because its populations had declined due to white-nose syndrome. The Indiana bat was listed as a federally endangered species in 1967 long before white-nose syndrome was identified.

All five of these state and federally listed bat species live in the insect control district serving Brandon, Leicester, Salisbury, Goshen, and Pittsford (BLSG). BLSG controls mosquitoes by killing larvae in standing water and spraying chemical pesticides along roads to kill adult mosquitoes.

The federally endangered Indiana bat has a large maternity colony at the northwestern corner of Salisbury and in neighboring Middlebury. Another colony is in Leicester. In the summer, females raise their young and spend the daylight hours on large trees. At night, Indiana bats fly throughout Salisbury, Leicester, and probably other BLSG District towns to feed on insects. Indiana bats are currently being studied in the BLSG District by Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department biologists.

While navigating the landscape at night, Indiana bats often fly along the edges of forests instead of flying through forests or across fields (more here). This behavior can result in Indiana bats flying along roads that follow the edge of forests. Road corridors through forests are also followed by bats.

One pesticide used by BLSG is malathion, a broad spectrum insecticide which is highly toxic to most types of insects and many vertebrate animals. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that malathion is “likely to adversely affect” the Indiana bat and most of the other federally threatened and endangered animal species. The EPA is currently being sued for failure to regulate malathion to prevent harm to threatened and endangered species.

One of the primary control practices of the BLSG Insect Control District is to spray a cloud of malathion along roads after dark. This toxic cloud floats over the roads at the same time bats are flying. It is therefore likely that due to BLSG’s practices the federally endangered Indiana bat will be directly exposed to malathion or will eat insects contaminated with malathion. This is exactly the type of situation which BLSG was required to report in its application to be authorized to spray malathion, but BLSG left that part of its application blank. This blatant omission was costly to local taxpayers; because of this gap in the permit application, a lawsuit was filed by Toxics Action Center in June 2018. Now BLSG is asking all the towns in the BLSG District to contribute more than $30,000 to cover its legal expenses for the ongoing suit.

The maximum penalty for harming or killing a federally endangered species is currently $49,467. That does not include legal fees if you contest the fine in federal court. BLSG does not have the resources to cover such expenses, but fortunately for them, local taxpayers do. This time around, select boards in most of the towns in the BLSG District have agreed to add to their budgets exactly what BLSG has requested to pay its attorneys. BLSG’s continued use of malathion might be putting the taxpayers in the District towns at risk of new legal expenses which dwarf the current BLSG legal bill just handed to the towns.

It is fitting that one of the towns, Salisbury, will let the residents decide whether BLSG should get additional money to pay its current lawyers. The proposed general budget for Salisbury will cover the town’s share of BLSG’s operating expenses, but a separate article on the Australian ballot will determine whether BLSG gets an extra $5,500 from Salisbury for its lawyers. The Salisbury Town Meeting vote on Tuesday March 5 includes Article 11, which reads:

‘Shall the voters appropriate $5,500.00 to the Brandon Leicester Salisbury Goshen Pittsford Insect Control District to fund their additional budget request to meet anticipated legal costs, in addition to the $20,000.00 included in the general fund budget to fund their operational budget?

A vote against this article will not affect the mosquito control activities in Salisbury but will send a message that Salisbury should not be held responsible for legal expenses caused by BLSG’s disregard for the environmental impacts of its practices.

Note: This post was published as a letter to the editor of the Addison Independent and prompted two editorials by the publisher and several other letters to the editor. These are all linked at this post.