Vermont Endangered Species Law

Vermont has the strongest state endangered species law in the country. The law specifically disallows activities that create a risk of injury to the listed plants or animals.

Creating a risk of injury to a listed species is referred to as “taking” or a “take.” A take is defined as “an act that creates a risk of injury to wildlife, whether or not the injury occurs.”

Employees of the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department also use the term “take” to mean documented injury that has already happened to an animal or plant. When discussing the potential injury to listed species in Vermont it is important to know which definition is being used.

Vermont’s threatened and endangered bats

Since 2001, biologists from Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Green Mountain National Forest have studied bat populations in the Champlain Valley. In Vermont, there are nine species of bat and five of them are on Vermont’s endangered species list. All five of the bat species on the endangered species list have been found in the towns of the BLSG Insect Control District. Multiple maternal roosting colonies of the endangered Indiana bat and other listed species have been documented in the BLSG District. Two hibernaculum sites, where the Indiana bat or other species spend the winter, has been documented in the BLSG District.

The threat posed by pesticide spraying

In the BLSG District, roadside spraying of the chemical pesticides malathion and permethrin happens during the same hours and the same months that all of Vermont’s threatened and endangered bats are active — after dark from May through September. The pesticides are applied using truck-mounted ultra-low volume (ULV) sprayers which create a mist of fine droplets of concentrated chemical which stays aloft for about two hours. The mist drifts about 150 feet on either side of the road and a similar distance upwards in concentrations high enough to kill flying mosquitoes and other mosquito-sized or smaller insects. Larger insects can survive the chemicals but may be contaminated with them.

Bats can be exposed to these pesticides as they fly through the mist by breathing the droplets or contacting them with their wing membranes or fur. Bats can also be exposed by eating insects contaminated with the pesticides. Subsequently, other bats can be exposed by social grooming (licking the fur) or through mother’s milk.

On a typical evening of roadside spraying in the BLSG District, a mist of chemical pesticide may remain suspended over about 1000 acres for two hours. Bats on Vermont’s endangered species list have been documented flying along, adjacent to, and above many of the roadside spray routes in the BLSG District (see figure below).

More information about the threat to bats from pesticide spraying can be found in the Arrowwood Environmental 2020 report “The BLSG District’s Use of the Adulticides Malathion and Permethrin: Impacts on Five Threatened and Endangered Bat Species.”

Provisions for critical activities that might harm endangered species

If a critical (e.g., economically important) activity risks harm to an endangered species, the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources may require an “incidental taking permit” to allow the activity to continue legally. Such permits define how the activity might harm the listed species and specify how harm should be mitigated, for example, by altering the activity.

Incidental taking permits can be granted if:

- the taking is necessary to conduct an otherwise lawful activity

- the taking is not the purpose of the activity

- the impact of the taking is minimized, and

- the taking will not impair the conservation or recovery of listed species.

Incidental taking permits are critical tools which allow the Agency of Natural Resources to ensure protection of listed species while allowing important activities to continue.

Simple modifications to BLSG’s practices can reduce the threat to bats

Three types of changes to BLSG’s roadside spraying operation could protect bats while continuing to provide the public service of mosquito control.

- Modifying where pesticides are applied: Roadside spraying in the BLSG District is currently done on 190 miles of roads which are mostly rural. Spraying could instead be limited to road sections with higher residential density so it has the greatest impact per mile on reducing mosquito-human encounters.

- Modifying when pesticides are applied: Roadside spraying is currently done when one or more mosquito traps or a sweep of a hand net captures at least 15 mosquitoes, or when residents complain about mosquitoes. Spraying could instead be triggered with more definitive scientific monitoring and only when mosquito populations are unusually high or if the Vermont Department of Health approves spraying in response to a public health emergency.

- Modifying the proportion of effort dedicated to controlling mosquito breeding versus killing adult mosquitoes: The only other insect control district in Vermont is the adjacent Lemon Fair District which controls mosquitoes by manipulating breeding areas and applying bacterial larvicides to breeding areas. There is no evidence that this successful approach, which uses no chemical pesticides, would not be equally successful in the BLSG District.

Mosquito control differs from agricultural pesticide application

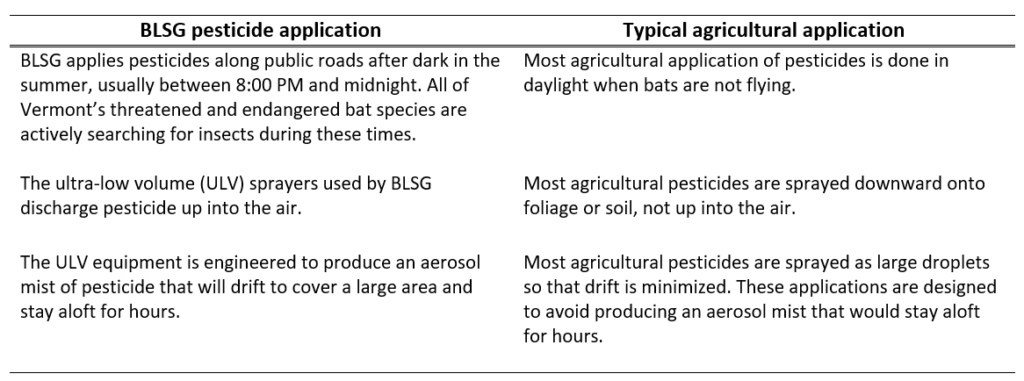

Roadside spraying of pesticides to control adult mosquitoes is a threat to bats because of when and how it is done. This protocol differs from that of most agricultural and silvicultural spraying in Vermont.

The combination of the above characteristics of BLSG’s roadside spraying cause it to be a unique threat to bats. It is uncommon for agricultural or silvicultural spraying to happen at nighttime and uncommon for it to be done with ULV sprayers. The combination of both nighttime and ULV spraying might occur in Vermont only when the BLSG Insect Control District does roadside spraying.