Scientists on the Vermont Endangered Species Committee are currently considering the risk that BLSG’s roadside spraying poses to the five species of bat on Vermont’s endangered species list. The roadside spraying for mosquitoes happens after dark on summer evenings at the same time all of the listed bat species are flying low over the landscape hunting for insects. The pesticides used are malathion (an organophosphate) and permethrin (a pyrethroid). The sprayers (ultra-low volume or ULV) are engineered to produce a fine mist of tiny droplets that stay in the air for an hour or two and can drift away from the road in that time.

We don’t know how harmful this is for bats, but creating an aerosol mist of concentrated droplets of chemical pesticide at the time and place that bats are known to be flying is likely to create considerable risk. A 20-page report explains why this could be deadly for bats. The Vermont Department of Fish & Wildlife will have to decide soon whether this risk to endangered and threatened species is acceptable considering the benefit produced by the spraying.

Video above: I have never taken video of the spray trucks in the BLSG District but I found the New York City video above on YouTube. The ULV sprayers are effective in urban and suburban areas where a grid of roads allows a large contiguous area to be treated. This type of sprayer is not very effective along rural roads where mosquitoes can quickly reinvade from untreated areas.Although the ULV technology was designed for urban and suburban settings where it can be effective in killing some proportion of the mosquitoes that fly through the mist (it doesn’t kill resting mosquitoes), in the BLSG District it is used mostly on rural roads. Mosquitoes killed along isolated rural roads can be replaced within hours from outside the ca. 300-foot wide spray swath. Especially when there are few residents along these roads, any harm to bats happens while people receive very little if any benefit. The Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department will have to weigh the risk to endangered bats against the minimal reduction in human-mosquito encounters provided by spraying these roads.

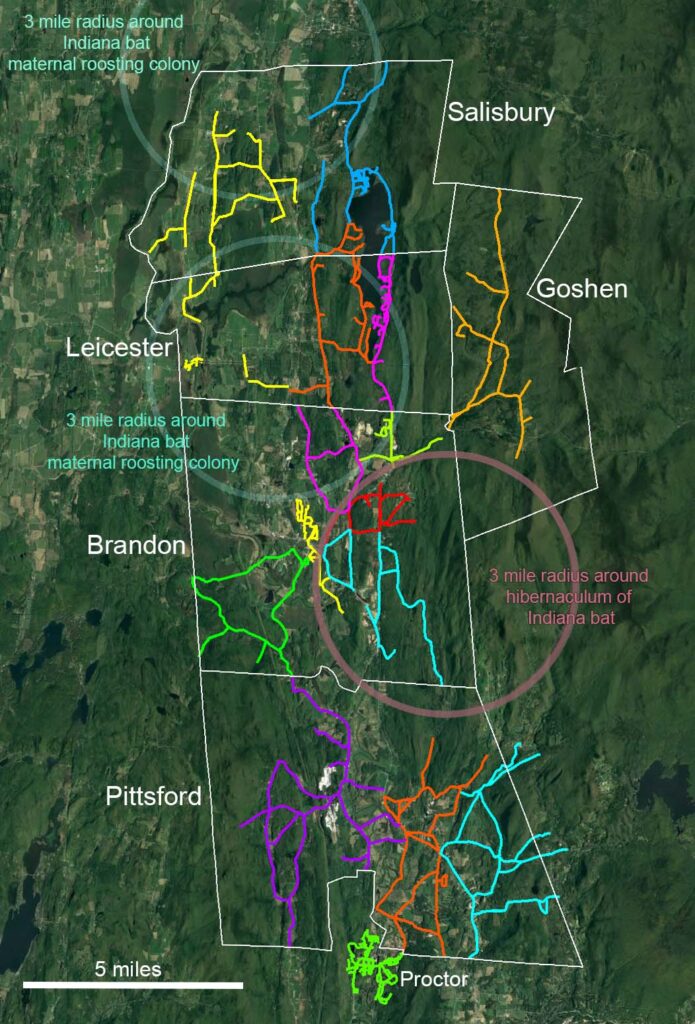

The five towns of the BLSG District (white borders) and the pesticide spray routes in each town (each colored line is a separate designated spray route about 5 to 15 miles long). The five species of bat on the Vermont endangered species list have been found in these towns. One of those bats is the federally endangered Indiana bat which has at least two maternal roosting colonies in the District (green circles are the areas where bats from the roosting colonies are expected to hunt for insects in the summer). The Indiana bat hibernates each winter in caves, mines, or other protected places including an abandoned mine in Brandon (pink circle is the 3 mile radius around the mine where Indiana bats are expected to gather in the fall and where male bats might spend the summer feeding).

The bats on Vermont’s endangered species list have been documented throughout the BLSG District by state and federal researchers. Before white nose syndrome began killing bats in 2007, the federally- and state-endangered Indiana bat had a large summer population in the District and some even hibernated locally (see figure above). Fewer of the listed bats are present now but most or all of the five listed species can still be found in the summer (see this post).

BLSG’s spray routes reach into some of the most important bat habitat in Vermont. On a typical night of spraying in the summer, a mist of chemicals drifts over about a 1000 acres of this habitat for an hour or two. Most of the risk to endangered bats created by this mist may not be offset by substantial benefit to people. There are several simple changes (when, where, and how to spray, see this post) that BLSG can make to reduce the risk to bats, so the decision facing the Vermont Department Fish & Wildlife should be an easy one.